THE SYMPHONY OF SHIFTING

Those of us in the financial business spend a lot of our time explaining why things happen. The volatility investors have been experiencing in the last few months and particularly, over the past month, is fodder for explanation bias. Unfortunately, fixating on seemingly logical ex-post cause and effect relationships can lead to a narrow-minded and distorted understanding of reality. And in the end, does little to ease the pain in your pocketbook.

The current list of explanations is as long as the number of analysts willing to offer a forecast. Take your pick; hawkish central bankers broadcasting the higher rates for longer theme, the disconnect between actual earnings versus expectations, inflationary implications of a robust labour market driving outsized wage settlements, unexpected economic growth despite eighteen months of rising interest rates, unbridled spending by governments whose endgame seems to be infinity.

What we need to understand is that past performance is just that. It tells us where the market has been but does little to tell us how long the market’s malaise will last and where it is likely to go. And since explanation bias is running rampant allow me to add another more simplistic possibility to explain current market action.

At the top of the list are seasonal trends, something we talked about in a previous commentary. Markets tend to underperform in August and September. October can be good or bad (it was bad this year). November and December are typically the best months for equity markets, especially if we see a so-called Santa Clause rally at the end of the year. So far, November has played out as expected.

Seasonal trends help explain the timing of moves but do not help us understand the cause-and-effect relationship. Which is to say, what is causing the untethered price action and how long will it last? In our view, the choppy price action in both stocks and bonds is related to a marked shift within institutional investors’ asset mix.

At the institutional level of portfolio management, asset allocation is the beginning and end game. Like a conductor at the symphony, institutional money managers navigate a delicate balance of instruments (in this case stocks, bonds, cash, and perhaps a touch of alternative investments) to produce the perfect harmony.

With that backdrop imagine that you manage a large pension fund. Billions of dollars in the investment portfolio. More than 100 million dollars coming into the plan every month that needs to be invested. And that only scratches the surface of this mega institutional market. The Harvard Endowment fund, for example, could finance a small country. The Canadian Pension Plan valued at nearly 500 billion dollars Cdn, is a medium size player in the North American pension market.

Unlike individual investors who struggle to define their objectives, time horizon and risk tolerances, pension fund managers rely on specificity based on actuarial assumptions. Demographics within the pension plan define the objective, managers assume an infinite time horizon and risk is quantified by portfolio size and variability. And in this world size matters!

Selecting individual stocks that may provide outsized gains for a retail investor would not scratch the performance surface in a large institutional portfolio. In the institutional mega portfolio stock selection takes a backseat to the plan’s asset allocation that defines the weight that should be applied to stocks, cash, and fixed income within the portfolio.

Now think about the asset mix in terms of fixed income investments. Until eighteen months ago, bonds provided no diversification benefit to the asset mix. Interest rates were at or near zero, which meant that rates had nowhere to go but up. As rates rise, bond prices fall which hampers investment performance. Given the limited diversification benefits of fixed income assets, by early 2022, most institutional portfolios were overweight equities and underweight bonds.

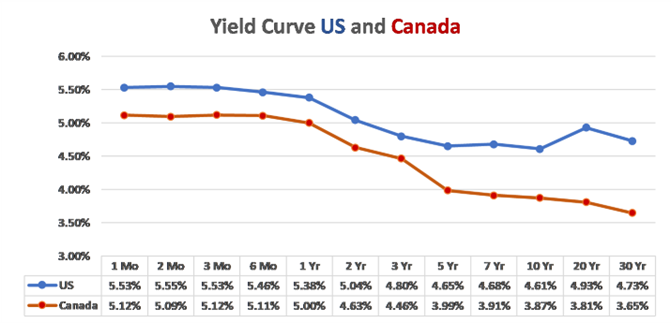

As central banks raised the overnight lending rate, bonds began to re-surface as an important asset class. Institutional investors began nibbling at the short end of the fixed income market (i.e., three-, six- and nine-month US treasury bills) through the remainder of 2022 and into the first two quarters of 2023.

But when the yield on ten-year treasuries (pension plans preferred point along the yield curve) touched 5% – which occurred in October and early November – institutions went all in. Mega-portfolio money managers began to normalize their asset mix by increasing exposure to short and mid-term bonds.

We witnessed this intraday shift often during brief periods in October. When the yield on ten-year US treasury bonds got above 5%, stocks declined, and bonds went up. As the ten-year yield declined, bond and stock prices stabilized until the yield again moved into the 4.9% to 5.0% range. Because institutional investors represent about 70% of the daily trading volume in US financial markets, the impact of this symphony of shifting cannot be understated.

CBOE US Ten Year Treasury Yield Index

Assuming we are correct in our cause-and-effect thesis, the point at which the impact of this asset mix shift is muted will occur when the supply and demand among ten-year treasury bonds normalizes. That should occur if ten-year US treasuries fall back to pre-September levels where the yield was 4.0% and 4.4%, or if rates back up to a level comfortably above the 5% demarcation line. In fact, the normalization process may already be underway, as equity markets began rallying about the time ten-year treasuries fell below 4.8% (see chart).

CUE THE MUSIC

“Navigating the Return-Yield Two-Step”

We have been fielding calls from clients about the seemingly poor performance of our conservative income mandate. This is a mandate that is typically comprised of value stocks paying above average dividends, plus an allocation to investment grade bonds and cash. Normally, this collection of securities would provide an above average tax-efficient income stream with below market volatility. But throw into the mix a prolonged period of rapidly rising interest rates, and the pain to one’s psyche is palpable.

We understand the pain and are acutely aware that interest rates and dividend stocks are connected by a series of warped dance moves that look more like a senior trying to put on a pair of socks than a highly synchronized Texas two-step.

Unfortunately, for the past eighteen months, the conservative income mandate has been subjected to a financial choreography where rising interest rates become the unexpected third wheel in a hot tango between returns and yields. To face the music from clients and the markets, we need to make clear how we intend to navigate through the next sequence of dance steps. So, without further ado… cue the music!

Dividend-paying stocks have a place in most portfolios because: 1) they fall into the value category which means they tend to be more stable than growth stocks, 2) managements’ generally increase the dividend on a regular basis which helps income-oriented investors stay current with inflation and 3) the regular distributions (usually paid quarterly, sometimes monthly) can add significantly to the portfolio’s overall return. The latter point is significant because, according to Standard and Poor’s, re-invested dividends are responsible for nearly 35% of the total equity return for U.S. stocks over the past 100 years.

We expect dividend stocks to outperform when interest rates are low (say 2009 through 2019) and to excel in an ultra-low-rate environment (i.e., zero interest rates) which we experienced during the Covid pandemic.

The challenge for dividend paying stocks occurs when interest rates are rising. We recognized that risk and assumed interest rates would rise because at the latter stages of the pandemic they were at or near zero and had nowhere to go but up. What we did not plan for was the size and accelerated pace of those rate increases.

Normally we would take the edge off by purchasing dividend paying stocks in sectors that are less likely to be impacted by rising rates. The financial sector being a case in point, where a rising rate environment generally improves loan margins.

Unfortunately, this time was different. For two reasons: 1) the Bank of Canada raised the overnight lending rate at an unprecedented tempo to combat inflation and 2) the surge in short-term rates led bond traders to assume that a recession was highly likely which caused the yield curve to invert.

Since banks borrow short-term and loan long-term (typically loaning out money for five to ten years for mortgage and car loans) their margins were pinched[1] which effectively undermined the diversification benefits typically provided by financial stocks in a rising rate environment. This time (see accompanying tables), banks followed the general downturn that was expected to negatively impact other sectors.

Rising rates have an adverse impact on the share price of value stocks because the interest paid by a bond becomes a viable alternative to the dividends being paid by the company. Bonds are more attractive because a failure to make an interest payment would lead to bankruptcy.

Dividends, on the other hand, are not guaranteed. A decision to reduce the amount of the dividend or worse, to eliminate the dividend, will have no impact on the viability of the company. It will, however, impact the value of the company’s stock.

The Impact of the Payout Ratio

Dividends are distributions made from after-tax profits by a company to its shareholders. While the amount of the dividend, and its’ frequency, are determined by the company, most follow a policy of paying quarterly dividends that are increased steadily over time.

That’s why dividend paying stocks are considered interest rate sensitive. More importantly, the companies that offer the highest dividend yields (dividend yield is the ratio of annual dividend divided by the share price, expressed as a percentage) generally have the biggest debt load. Companies that come to mind are utilities, telecommunications, and real estate investment trusts (REITs). Because these sectors are “interest rate sensitive” their value declines when rates are rising. The steeper the rise in rates, the greater the impact. The concern is that these companies will not be able to pay the current dividend which intuitively explains the high yield.

The objective when seeking out dividend payers is to calculate the probability of a dividend cut. What we look for are large-cap companies that can weather the interest rate storm so that when the rising interest rate cycle concludes, rates stabilize and eventually decline, the share prices will recover. As such, we avoid stocks where the dividend payout has an outsized impact on the company’s cash flow. We look for companies where the dividend is no more than 60% of the company’s profit.

THE BACK STORY FOR CANADIAN BANKS

After two quarters of negative GDP, there is real concern that the Canadian economy is entering a period of sluggish growth. We see that with the reaction from Canadian banks that are attempting to fortify their balance sheets against a rising tide of bad debts.

Normally we would expect the banks to tap the equity market by selling additional common shares, which has a dilutive impact on current shareholders. Fortunately, that does not seem to be the approach this time. Traditionally, the banks would issue shares to raise capital, but given that equity prices are down 5% to 11% year to date, selling new shares is not a great option.

Instead, Canadian banks have been cutting costs by freezing new hires, improving efficiencies, and selling assets in non-core business units. Think of it as a hedge against the possible headwinds should we see an increase in default rates on credit-card payments and mortgages.

According to Reuters, “Bank of Nova Scotia (Scotiabank) sold its equity stake in Canadian Tire’s financial services unit back to the retailer last month, raising $895 million Cdn. while BMO is winding down its indirect auto lending business and reportedly looking to sell its RV loan portfolio.”

Those sales represent a marked change from the spending spree that occurred between 2000 and 2019. During that period, the five largest Canadian banks spent about $147 Billion Cdn. on acquisitions including credit-card portfolios, wealth, and asset management firms, as well as smaller regional banks in the U.S. and internationally as a part of their aggressive expansion strategies. Since the beginning of 2023, most of those taps have been turned off.

The other consideration is the Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratio, which as of the third quarter was between 12.2% to 15.2% across the big five banks. While that is above the current requirements of 11.5%, there is concern that OFSI (Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, which is the bank’s regulator) will be pressured to increase the capital requirement as the economy slows.

OFSI does that by increasing the domestic stability buffer (DSB) which is currently at 3.5%. The next review is slated for December 2023, and analysts expect OFSI to increase the DSB to 4% sometime in the first quarter of 2024.

Notes Reuters, “Scotiabank, which has a CET1 ratio of 12.7%, indicated in August it was preparing for a higher capital requirement [in 2024].” It’s a similar story with Royal Bank of Canada, the largest of the big five. The challenge for Royal is to close the HSBC acquisition, while maintaining a CET1 ratio above 12%. So far, the bank says it is comfortable with these metrics.

The key factor for investors to watch is whether the big five banks raise their dividends in January. That has been standard operating procedure since OFSI allowed increase requirements to return to normal after eliminating the pandemic restrictions. Should the banks choose to freeze dividends at current levels, we doubt that would be seen as a negative. However, if any of the big five banks raise their dividends as is their normal practice it would be viewed as bullish. For now, it is a waiting game.

EMBRACING UNCERTAINTY

Knowing that most of us are risk averse, the notion that investors should embrace uncertainty is about as foreign as finding a polar bear in Death Valley. When you look at charts of individual stocks, their pattern looks a lot like the daily commute of a kangaroo. And trying to anticipate whether the next move will be up or down is like trying to decipher a foreign language written with invisible ink.

This is the landscape of the investment industry and knowing the challenges money managers face, does not alter the fact that we must constantly analyze the ebbs and flows of the economy, and attempt the predict the future armed with what we know as fact, what we think we know (opportunity) and what is unknowable (risk management through diversification).

It is a constant game of trying to ascertain where the puck is going, not where it is. Those who excel in this game strive to take advantage of uncertainty resulting from market fluctuations and outsized price volatility. Success is measured in the long-term performance of the portfolio against a reasonable benchmark. Underpinning this philosophy is the view that over time financial markets will deliver returns in line with historical averages.

The benchmark (we use one of the three Real-World portfolio Indices[2]) provides a mandate-based gauge that is tied to what average investors in Canada are doing with their portfolios. The Real-World portfolio indices provide a challenging environment having a twenty-year track record of generating first or second quartile returns. In short, a portfolio benchmark is appropriate and challenging. Unfortunately, if the investor is unaware that the manager is following a reasonable benchmark, then performance analysis and return expectations occur in a vacuum. When the pinnacle of uncertainty emerges and investors are confronted with performance attributes that did not meet an ill-defined objective, they can make decisions or encourage their manager to make decisions that may, in the long-term, not be in their best interest.

For example, we posited at the end of October that the rate hiking cycle had concluded, and sentiment had reached the pinnacle of irrational fear. As irrational fear morphs into unbridled greed markets will provide the capital appreciation that eluded investors during the past eighteen months. Aside from say, the mega-cap tech companies that provided all the upside oomph within the S&P 500 during 2023.

Simply stated, we think the companies that did not participate in the upside pull of the mega-cap tech names (note the mega-tech companies that had huge balance sheets and did not have to borrow capital in a rising rate environment) will play catch-up in 2024.

We always hedge against uncertainty through diversification that allows us to spread risk across different asset classes and sectors. Notable within this spectrum has been the return of fixed income assets as an optimum diversifier.

As always, investors should focus on a long-term perspective. Embracing uncertainty encourages portfolio managers to explain the short-term impact against a long-term backdrop. Short-term market fluctuations become blips on the long-term trajectory. Uncertainty is noise that distracts from the growth potential of investments… embrace it don’t fear it!

Uncertainty drives innovation and change. Investors who are open to uncertainty are more likely to invest in emerging industries and technologies, which can provide significant growth opportunities. For example, Tesla is trying to develop autonomous driving taxis within the next fifteen years. If the company is successful Tesla would dominate a multi-billion dollar market. We suspect the longer-term potential is what has helped Tesla’s stock to trade at levels that are not supported by current fundamentals.

Hopefully embracing uncertainty helps investors develop psychological resilience. This can lead to better decision making and less emotional reaction to market fluctuations. That’s why working with an Advisor plays a critical role when staring into an abyss.

Uncertainty when paired with experience lays the groundwork to learn and grow. Managers continuously research and adapt their investment strategies, which when explained to the investor, can lead to improved financial knowledge and skills over time.

Uncertainty often leads to herd behavior in financial markets as do-it-yourself investors follow the same trends. Those who embrace uncertainty should seek out contrarian positions (note our discussion on banks), which can be profitable when the consensus view is proven wrong.

During uncertain times, many assets become undervalued due to market pessimism. By embracing uncertainty, we can identify undervalued opportunities which potentially benefit portfolios when sentiment improves.

Economic and market cycles are intertwined, most notably during periods of uncertainty. That works both ways whether markets are rising or falling. Recognizing the existence of these cycles and embracing the changes with an eye towards the future is a natural part of portfolio management.

It’s important to note that embracing uncertainty doesn’t mean being reckless. Prudent risk management through optimum diversification, maintaining a keen focus on the financial objectives of the investor and applying a well-thought-out investment strategy, can do wonders for one’s pocketbook.

Richard N Croft

Chief Investment Officer

[1] For more information on the impact rising rates and other factors had on the banks performance you can watch a video we did for clients that explains the headwinds that impacted banks and why those headwinds would become tailwinds in 2024.

[2] The Real-World indices can be found on our website www.croftgroup.com